August 25, 2022:

Political graffiti and street art in general have a huge presence in Santiago, and in Chile in general; Valparaiso is well known for its gorgeous spreads and the colorful pieces that decorate its buildings.

In case you weren’t aware, Chile is currently in a very interesting position politically. This Sunday, September 4th, the citizens will be voting on a new constitution. When I arrived here on July 25th, there were many signs and scrawlings declaring “Apruebo!” (approve) and “Rechazo!” (reject) on various buildings and storefronts, and all of these markings are in relation to the September 4th election.

As someone very interested in civic activism and politics, I was intrigued to learn that voting for the constitution is obligatory in Chile. The country seems to reflect similar political divides as many other nations: parties more or less divided by class and socioeconomic status. For example, the neighborhood where I live almost exclusively boasts “Apruebo!” art and demonstrations, whereas the neighborhood where our IES Abroad Center is located, further to the north, has a mix of announcements. The country in general is very divided, just as it was when the votes were conducted for the current President, Gabriel Boric, who won with 56% of the vote, and the vote to end the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, which passed with 56% as well. When Boric was elected, about 8 million people voted—this election, over 10 million people are expected to cast their votes.

In 2019, there were huge protests and general political uproar about human rights and against the government. Boric rose to popularity and got elected due to his activism during those riots, and is now the youngest person to be President of Chile at 35. The new constitution that is up for approval was drafted as a result of the 2019 demonstrations and was written in 2021, the same year that Boric was elected. This is the first constitution in Chile that includes in its writing women, as well as the first to include indigenous populations. The polling places are divided differently this year, and people of different genders are sometimes able to vote in the same center, which was not the case previously. More young people, women, and indigenous people will be voting on this referendum than there have ever been before. A big question concerning this election and the fact that voting is obligatory is the idea that the true thoughts of Chilean citizens might be heard, and the real Chile should be revealed politically.

Salvador Allende, the President before Pinochet’s military coup d’état, was elected on September 4th, which is the same day as this year’s plebiscito. The current—and potentially soon to be previous—constitution, was written and put into place during the dictatorship, which makes the event that much more significant historically. When Pinochet created his constitution, the idea of “the right to” that Allende had established was wiped out and replaced with the idea of “access to services.” The currently drafted constitution reinstates the concept of citizens having “the right to” things, including housing, work, and quality healthcare. No matter what the people vote for, history will be made, and there will be an impact felt throughout the nation and the world.

September 4, 2022 6:30 p.m.:

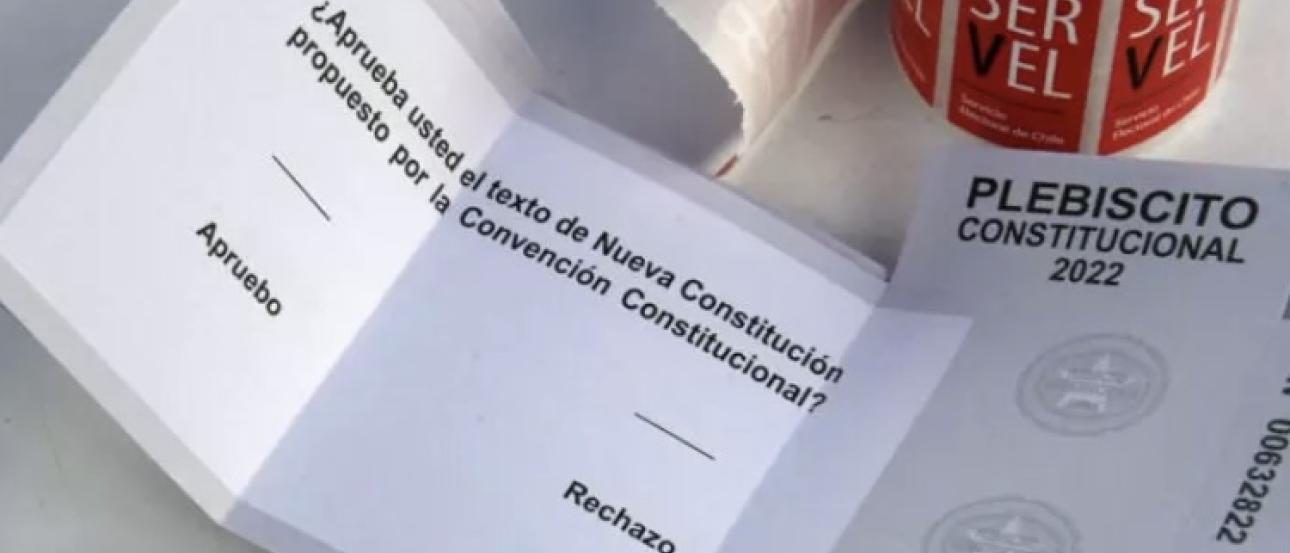

The radio is on and declaring “Apruebo” and “Rechazo” as each voting center counts its votes—by *hand*—and figures out if the constitutional referendum will be put into place. One of my friends is serving as a ‘vocal de mesa,’ which is the Chilean equivalent of an election judge, something I’ve done many times in Chicago. The ballot for this election includes only one question: “Do you approve the text of the New Constitution proposed by the Constitutional Convention?” and then below that, the options “I approve” or “I reject.” I asked for a sample ballot and was told that was not a thing in Chile—and that my friend would get in big trouble for taking one. Makes sense; not going to test it.

In our elections in Chicago, there are specific ballot types, which can sometimes be versions of the same thing, or be based on political party. They are always the same size, unless the ballot is provisional, and I have never seen one with just one question on it. The polls here open at 8:00 a.m.—my friend left just 30 minutes before the election began to go to the polling place, which baffled me because we have to set up the night before and the morning of when we run the elections in Chicago. The results are expected to come out by 8:00 p.m.—only two hours after the polls closed at 6:00, which is also a shock, because in Chicago, we’re lucky if we’re done closing the polls and delivering the results by 9:00 p.m. (voting also ends at 6 in Chicago), much less having accurate and complete results before then.

September 4, 2022 7:20 p.m.:

Right now, 37% of the votes are to approve the constitution, and 72.98% of citizens have rejected the referendum. 62% of votes have been counted.

September 4, 2022 8:10 p.m.:

They are still counting, and currently 38% have approved, and 72% have rejected the proposed constitution. More than 4 million votes were for, and over 6 million citizens were against. 88.68% of votes have been counted. The election has already been called, and speeches are being made. Many of the speakers are reminding listeners that the construction of a new constitution is not over, and that the processes to revise the current constitution will continue. I can hear people chanting outside as I listen to more results and opinions on the radio. Car horns and wolf whistles echo in the night.

September 4, 2022 8:30 p.m.:

My host brother also served as a ‘voice of the table,’ and was disheartened by the results of the plebiscito. He just got home, two and a half hours after voting finished. Thirteen million Chileans voted.

September 4, 2022 10:10 p.m.:

Different types of sirens can be heard in the distance outside every window of the apartment. It feels like the neighborhood is holding its breath in expectation. We’ll see what tomorrow brings.

September 6, 2022:

My Human Rights in Latin America professor says that the constitution was rejected because the people didn’t want real change. If you saw any news about Chile in 2019, you’ll know about the riots and demonstrations for social change that took place. A lot of people are sad that these events didn’t make the impact they had hoped for after the struggles they experienced. According to him, these results were highly unexpected.

September 11, 2022:

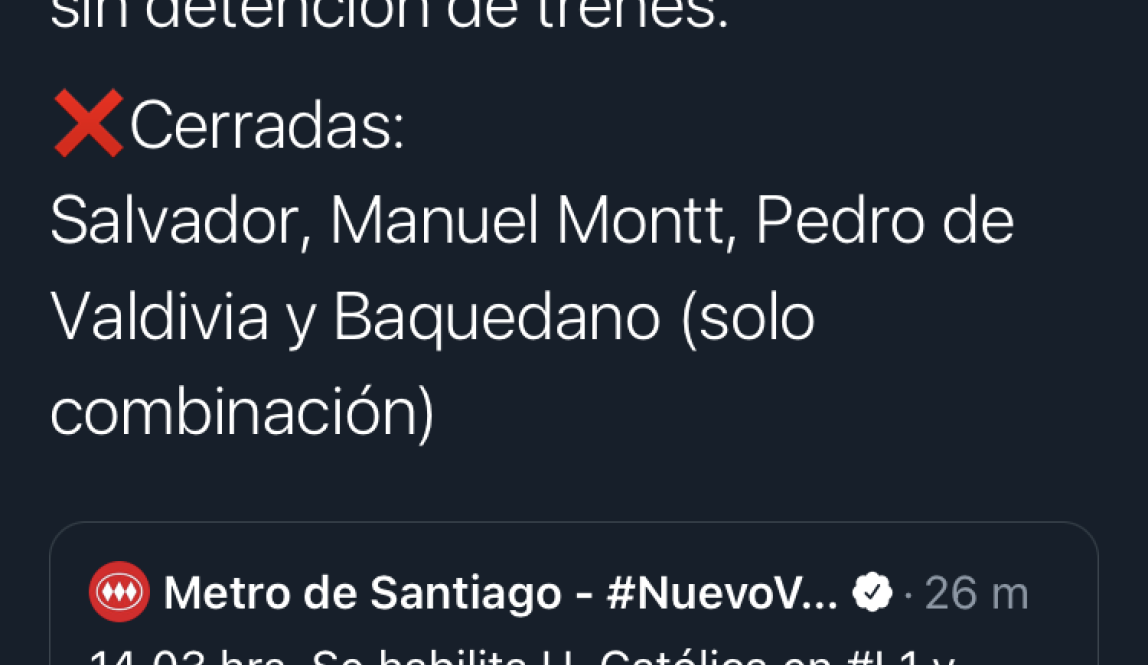

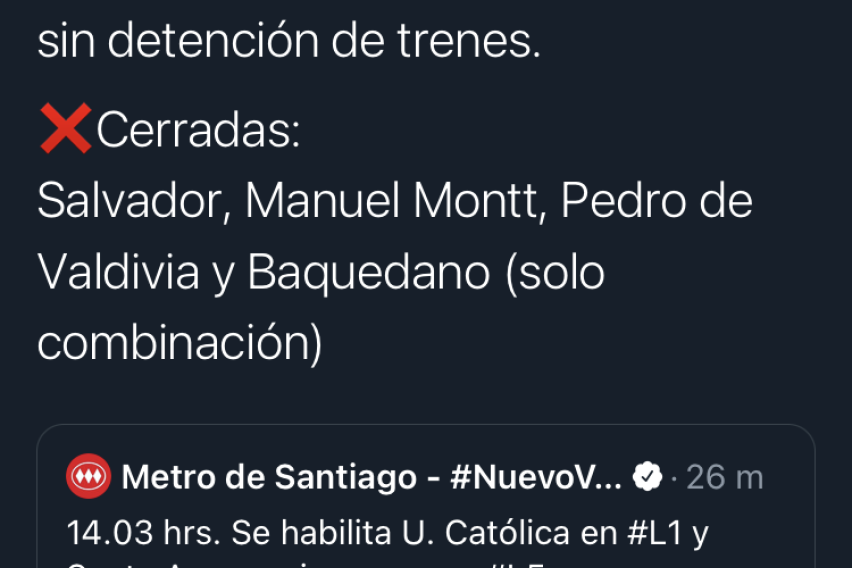

This day is an important anniversary in Chile. The military coup d'état marked the first 9/11 in world history in the year 1973. Protests would’ve happened even without the referendum results. All week elementary schoolers and high schoolers have been manifesting in the city center where the 2019 riots took place, which in turn has caused many subway stations to pause operation.

October 4, 2022:

Today, a month after the referendum election, the city has calmed down a lot. Every now and then there will be protests or metro stations will be closed, but in general, the results have settled in. I personally am very curious to see what happens for the next Constitutional Convention and what changes they will make. We´ll have to wait and see.

Maggie Peyton

My name is Maggie and I'm from Chicago, Illinois (one of the best cities in the States in my completely unbiased opinion). I'm left-handed, could watch Encanto every day, and I am a huge fan of the singer-songwriter Mitski. I study Public Policy at the University of Illinois in Chicago and am excited to learn more about Santiago. I hope to find a community away from the one I have at home and make Santiago my own.